But football had ceased to be the important thing in life for me. Britain and Germany were at war, and playing football was no longer such a thrill. Tommy Thompson, Tom Wilson and myself joined the Cyclists Corps at Sunderland. Later we were drafted to France, with Tom Wilson going to the 5th Battalion West Yorks while I went to the 8th Battalion. We still kept in close touch. In fact, we were frequent rivals on the soccer field because Tommy Wilson was the captain of his battalion and I skippered mine. They were worrying and uncertain days, and football helped me to escape from periods of mental depression. In the last month of the war I was among a crowd of Tommies to get gassed. I was sent home to Sheffield Hospital. I made a good recovery, but was ordered a few months' convalescence at a health resort.

The war was now over, and Sunderland were playing in the Victory League. I had already called at Roker Park before going on convalescence, and then by coincidence I met the team en route for a match against Durham City. They were a man short and manager Bob Kyle asked me to help them out - at centre-forward !

I should have refused. I was not fit and I was not a centre-forward, as I had learned to my cost in the first trial Sunderland had given me, but I was so anxious to pick up the loose threads and try and get back at Sunderland that I foolishly agreed. You can be too obliging and too anxious. I played badly. I didn't expect to get a game immediately afterwards, but I was hurt when I learned that my poor display meant I was never to play for Sunderland again. The directors had decided that my war experience had finished me as a footballer, and I was not offered terms. I walked away from Roker Park completely dejected. How different to the morning in August 1914 when I had hung around outside the ground, nervous yet full of hopeful ambitions. Now I felt bitter for the first time in my life. I was twenty-three, suspect in health and, worst of all, unwanted at Sunderland.

My old friend Tommy Wilson suffered a similar fate as myself. When he returned from the Army, Sunderland gave him a free transfer but he was quickly signed by Huddersfield Town. I wasn't so lucky. For some unknown reason Sunderland, although not wanting me, hadn't placed me on the free transfer list. Rumour travels quickly, and when one or two managers who may have seen me with Sunderland reserves showed interest, they were completely discouraged by exaggerated stories of how my health had suffered as the result of German gas. I became more and more despondent as I reflected how cruel fate had been to me. It seemed all my boyhood ambitions had been shattered and I was finished before I had really started.'

|

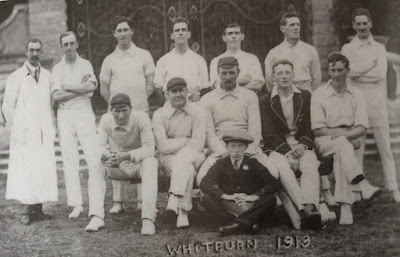

| Jimmy is back row, third from the left |

[It was later revealed that the manager of the Mid-Rhondda Football Club had asked Sunderland for the names of any surplus players, and that the Sunderland directors had recommended Seed]

It wasn't what I wanted because it meant that at twenty-three I was stepping out of the Football League, and I realized that the step back into top-grade soccer was a far more difficult move. But what could I do? Wasn't it better to have a go in Welsh football? At least I would be able to judge whether or not I was sufficiently fit to play the game again. Also, I had heard about the terrific soccer boom that had started up after the war in Wales and that several well-known League players were doing well down there. So I wrote to Haydn Price saying I would be glad to join Mid-Rhondda.

Thus, I packed up my troubles in my old kit-bag and decided to try my soccer luck once again, this time in a lower grade.

When a man gets backing he begins to feel good. My health improved and I soon struck up a happy understanding with Frank Pattison, the right-winger, who had also played for Sunderland. I was greatly encouraged, too, by Joe Bache, the old England international who was captain of Mid-Rhondda. Joe's wisdom was like that of an elder statesman. His best playing days were behind him but his generalship and captaincy made him the hero of the fans, and I learned more about the art and responsibility of a skipper from Joe than from anybody I know. It served me well later when I was to become captain of Sheffield Wednesday.

.jpg) The strength of the club at the time is best gauged by the challenge matches the team undertook against Football League clubs. Due to the large following the club possessed, they were able to offer incentives to league clubs to travel to Tonypandy. These were teams that normally played Bristol on the Saturday, then brought their first teams to the Rhondda for a Monday night encounter. Crowds in excess of 15,000 and the substantial win bonus that was offered elevated these games above friendlies. These encounters included wins over Nottingham Forest (3–1), Derby County (2–0) and Portsmouth (1–0) in 1919, a draw against Tottenham Hotspur and a narrow loss to Aston Villa (1–2) in 1920.]

The strength of the club at the time is best gauged by the challenge matches the team undertook against Football League clubs. Due to the large following the club possessed, they were able to offer incentives to league clubs to travel to Tonypandy. These were teams that normally played Bristol on the Saturday, then brought their first teams to the Rhondda for a Monday night encounter. Crowds in excess of 15,000 and the substantial win bonus that was offered elevated these games above friendlies. These encounters included wins over Nottingham Forest (3–1), Derby County (2–0) and Portsmouth (1–0) in 1919, a draw against Tottenham Hotspur and a narrow loss to Aston Villa (1–2) in 1920.][The JS Story:]

The grounds at Porth and Ton Pentre were very small. The river ran alongside the Porth ground and a man was specially appointed to retrieve the ball whenever it was kicked into the water, which was frequently. And the mud! It was up to your eyes in mud. I smile today when I read of managers discussing heavy grounds. Believe me, you don't know the meaning of the word unless you have played football in the valleys of South Wales. Hardly ever did I play on a dry pitch, but the conditions suited me splendidly because my training at Sunderland plus my Army life and the football in France had helped me to develop physically. I don't know what would have become of me had I gone to Mid-Rhondda in 1914 when I was a slip of a lad. Probably the name of Jimmy Seed would never have been heard in football again.

Before my playing days were to end I took part in some thrilling matches for England and Cup Finals and League Championship games for Tottenham Hotspur and Sheffield Wednesday, but none of these was more exciting than an F.A. Cup preliminary round match between Mid-Rhondda and Ton Pentre. At the time we were carrying all before us. Ton Pentre is situated some three miles up the Rhondda Valley from Tonypandy where our team had its headquarters. The rivalry was terrific and there was little else discussed in the miners' pubs and clubs a week before the match.

While Ton Pentre were almost invincible on their own small ground, we were favourites on our home pitch. It seemed that every miner in South Wales was present on the Saturday. Somehow or other, 28,000 soccer-crazy Welshmen squeezed into the ground, and the mountainside overlooking the field was black with spectators who couldn't get inside. It must have been one of the largest crowds ever gathered for a sporting event in the Welsh valleys and, believe me, there was more excitement from this crowd than from any huge gathering I have since witnessed at Wembley, Hampden Park, Ninian Park or Windsor Park. Within a minute we were one up when a centre from Frank Pattison on the right wing was turned into the Ton Pentre goal by Patsy Gallagher, the 'Ton' centre-half and skipper. Our supporters just went crazy. They invaded the pitch singing, shouting, waving hats, and rattles. Others hugged and embraced the home team. The referee could not re-start the game because many excited fans who had come on the pitch decided they had a better view around the touch-lines, and it was five minutes before the game started once more, with thousands of spectators now around the edge of the playing pitch.

We didn't hold the lead for long and 'Darky* Lowdell, the visiting inside-right equalized, and Darky silenced our supporters with the winning goal in the second half.

Lowdell was attracting much attention from the scouts of first Division clubs and it was rumoured that Peter McWilliam of Tottenham Hotspur was one of the interested parties and had made several trips to South Wales to see for himself. I envied Darky because, happy as I was with Mid-Rhondda, it surely was natural that I pined for top-class football. It was while reading rumours of McWilliam's interest in Lowdell that I decided to write to Sunderland to ask that I might be given a free transfer because, although I had permission to play for Mid-Rhondda, my old club still had my name on their books. I was almost surprised when my request was granted by return post. I felt this matter to be important because at least I might get to a Third Division League club now that there wasn't any transfer fee hanging over my head and I was free to go anywhere I liked.

Then the surprise came. Towards the end of one season with Mid-Rhondda, Peter McWilliam asked me: 'How would you like to join the Spurs ?' It was like a dream. Discarded by Sunderland before the start of one season, and now wanted by the famous Tottenham Hotspur club at the end of the next. It hardly made sense. Sunderland must have been dumbfounded. When they heard about Spurs' interest in me they were displeased, and efforts were made to get me to return to Roker Park. It might have been difficult for me to have joined the London club but for the fact that I had taken the precaution to get permission for a free transfer in writing. After McWilliam saw this document he pointed out politely but quite firmly that I was free to join any League club I liked as Sunderland no longer held any claim on me. It was a lesson that I never forgot, and when I became a manager I never came to any quick decision about a player being finished after he had gone through a bad patch.

But it wasn't Sunderland who really held up my transfer to Tottenham. The big objection came from the Mid-Rhondda supporters. The Welsh club hadn't enjoyed such a successful season for years and when it became known that Spurs had made attempts to sign me, the Mid-Rhondda fans figured this might mean the breaking-up of their successful little team with wholesale departures to League clubs. They were particularly angry with Peter McWilliam, but they were also displeased with the management of Mid-Rhondda. They had it in their heads that I was not a willing party to the transfer, but had been more or less forced to join the London club in order to assist Mid-Rhondda financially. They didn't mean to let me go without a fight.

I made my last appearance for the little Welsh club in a midweek match against Llanelly. The game passed without incident, but the crowd gathered at the back of the stand at the finish and began to let the management know what they thought about them because they had agreed to sell Jimmy Seed. It wasn't any secret around Tonypandy that a band of loyal and angry supporters had planned to grab McWilliam as soon as he showed his face, and duck him in the soggiest patch of that muddy field. They waited, believing the Spurs manager to be in the dressing-room when the game ended, but Peter had been tipped off as to what was in store for him, and the gentleman was not available for ducking.

The crowd would not go home, and began to chant and jeer. A member of Mid-Rhondda appealed to me to go and speak to them and to explain that I was going to Tottenham entirely of my own free will and there wasn't any question of my being handcuffed and sold into bondage. So I went out and faced the crowd. There was an immediate hush, and there wasn't any antagonism when I explained that the move to a big club was for the good of my own career, and that while it was helping me the money would also help Mid-Rhondda F.C. They quietened down and, although not entirely satisfied, allowed everybody to leave in peace. But the football fans of Mid-Rhondda never forgave Peter McWilliam. When in later years we discussed my signing he told me he had disguised himself when looking at players along the Rhondda Valley. Certainly, it is a fact that when he returned to the area after signing me to take another look at Darky Lowdell, he put on spectacles and a false moustache to avoid any mud-slinging !

Strangely, McWilliam first spotted me when making the journey to Wales to watch Lowdell. Years after when I was to join Sheffield Wednesday, Spurs exchanged me for Lowdell who had been snatched from Wales by the Yorkshire club. Spurs got their man in the end!

Luck plays a tremendous part in man's success, and you can apply that to any walk in life. After I had become a manager I met Peter McWilliam, and while recalling the day he signed me from Mid-Rhondda at the expense of Sunderland, I wisecracked: 'Are you still lucky?'

'Lucky?' he asked with a smile. 'You were the lucky one, Jimmy. I showed judgment. If I hadn't spotted you, you would have spent the rest of your career in third-class football in Wales!' Peter McWilliam was probably right.

Major Prior, one of the directors, and the club doctor called me in to see them later, and the major said: "No man who has been through two gassings is good for top-class football.

"Forget the game, sonny. Have a rest, and then start back in the pits. That way you will stay fairly healthy and not strain your body."

Seed's mind went back to the days before the war when, just in his 'teens, he had gone down into the Durham coalfield from his Whitburn home and worked for a few shillings a week.

Better than the pits

"For a brief while before going into the Army I had sampled the life of a professional footballer," he told me. "I liked it much better than the pits. Those words of the Sunderland directors seemed almost savage at the time."

For a while Seed pottered about in Whitburn, where he was raised doing a bit of labouring and playing with the kids among the slag heaps to get himself fit.

Most weeks he would call on the Sunderland club. Then he was told that the Welsh club Mid-Rhondda were willing to give him a trial.

"I ran all the way home. The packing didn't take long. It never does when you've only got one suit. Next day I arrived in South Wales and I began playing straight away."

The pay was not lavish. But it was supplemented in a small way by an Army pension granted after those gassings at Nieuport, in Belgium, and Valenciennes.

"The extra came in handy," Jimmy smiled. "Then, one day, they called me for a medical.' First they asked me what I did for a living, and I told them. They said that anyone who played football must be fit, and my pension was stopped."

Seed the Fighter became a Mid-Rhondda favourite. Then in 1920 Peter McWilliam, of Tottenham Hotspur, offered him a full-time footballing job at White Hart Lane.

Within a year he had helped scheme Spurs to a Cup Final win over Wolverhampton Wanderers. His great pal, Jimmy Dimmock, scored the winning goal, and the boy from the Durham pits celebrated with champagne.

It took a man of courage and character to pull himself up out of the gloom of these post-war days when his health was bad, and the future looked black.

And it needed great modesty to hide from everyone except his wife the fact that those gassings still took their toll through the years, when the English winter was at its worst and the damp and the rain brought the pains to his chest and the aches to his head.

"I have never been really well. When I had to take time away from the club, I always said I had a cold."

Jimmy Seed never felt it wise to let the players he led to so many great triumphs know that those days in Flanders and France still occasionally took their toll.

For, as he puts it, "You've got to be fit in football. And if you are not, keep telling yourself you are. It’s surprising how well it works.”

Jimmy Seed signed this Spurs publicity photo and added a dedication to Haydn Price, his former manager.

Wiki:

They had a successful time in the seven months that Seed was with them, winning both the Southern League Division Two and Welsh League titles.

Mid Rhondda FC was based in Tonypandy, a colliery town most famous for the Tonypandy riots.

'Brought to Mid Rhondda by Haydn Price'

Goalkeeper Harry Moody was born in Rochdale (Moody had won a DCM for gallantry on active service) and Jimmy Carmichael, although signed as a centre-half, soon gained a reputation as a marksmen, once scoring seven goals in a game.

But McWilliam was more interested in Seed instead.

%20-BLOG%20Copy.jpg)

.jpg)